There's a better video of an octopus pretending to be a rock out there somewhere, but this is pretty damn amazing of overall camouflage ability:

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Too Many Words About Piketty

Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty

Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas PikettyMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

Tackling wealth and inequality, this was one of the best selling and least read books of the summer. Not that I'm mocking anyone here, I kept putting it down and took perhaps 5 months to finish and another month to get motivated to write this review (which is itself open to criticisms based on length).

It's a strange book to be a best seller. It's got three sections which basically consist of an idea, some data, and a policy pitch. More on the idea and policy pitch below, but the data section is interminable. The detail is something I respect on some level but if you're not the sort to read about national income level comparisons between different states and time periods already, I think you could do with perhaps three charts and a comment along the lines that "Similar trends were seen by most nations. Most other factors were minor."

Oh, also it's not really focused on inequality.

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Watership Down

This wasn't in our household as a kid so I read if with no nostalgia factor. In fact, I knew so little about it that I assumed there was water and ships involved. As well as rabbits, which I somehow knew. Maybe all the rabbits got on a boat and had whacky adventures or something? Well, no, and the title is definitely *not* referring to something capsizing.

My unbiased, cynical opinion for those who read it when they were 12 and have fond memories: You are 100% correct. This is just a great adventure book, written by someone who is clearly fond of adventures, humans and rabbits all at once. (Could be nicer to dogs & cats though.) You get camraderie and perseverance and watch characters grow into roles thrust upon them by circumstance. Hazel, not the strongest or the smartest, becomes such a great leader in such a plausible way that I was totally unsurprised to find that any number of people are willing to give you management lessons based on the book. The chapter where Bigwig stands his ground is worth the price of admission on its own--it's the most thrilling performance by an underdog in a literary fight since Enkidu went 15 rounds against Gilgamesh and drew a majority draw. Could have used more female rabbits, and one good joke gets used twice, but those are perhaps the only mis-steps I saw.

Bottom line: Read this book if you haven't, get it for your kids if there's not a copy in the house.

My unbiased, cynical opinion for those who read it when they were 12 and have fond memories: You are 100% correct. This is just a great adventure book, written by someone who is clearly fond of adventures, humans and rabbits all at once. (Could be nicer to dogs & cats though.) You get camraderie and perseverance and watch characters grow into roles thrust upon them by circumstance. Hazel, not the strongest or the smartest, becomes such a great leader in such a plausible way that I was totally unsurprised to find that any number of people are willing to give you management lessons based on the book. The chapter where Bigwig stands his ground is worth the price of admission on its own--it's the most thrilling performance by an underdog in a literary fight since Enkidu went 15 rounds against Gilgamesh and drew a majority draw. Could have used more female rabbits, and one good joke gets used twice, but those are perhaps the only mis-steps I saw.

Bottom line: Read this book if you haven't, get it for your kids if there's not a copy in the house.

Saturday, November 29, 2014

The Year Civilization Collapsed

1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. Cline

1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed by Eric H. ClineMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

The late Bronze Age had a remarkable trading network established1--ships were sailing hundreds of miles to move goods around different polities the eastern and central Mediterranean, including pottery, fabrics, copper and tin. The was the age of the palaces and kings that Odysseus would have lived in and that gave rise to tales of the Trojan War.

Around 1177 BC, the Sea Peoples descended out of nowhere (or maybe Sardinia and Sicily) and looted cities across the region, hitting places so quickly that pleas for help were written but messengers didn't have time to leave the city with them. Ramesses II of Egypt was able to defend his state, but every where else succumbed and absent trade civilizations withered.

Except not quite. Cline says that recent archaeology suggests cities' destruction might span a century from perhaps 1200 to 1130 BC. And some of the destruction was by earthquakes, probably, and when there was violence it's not clear whether it was internal or external and when it was external often we can only speculate as to whether it might have been the Sea Peoples. There was a collapse but the causes (all of the above, plus drought and climate change) can best be summarized as "it was complicated." Cline eschews sensationalism and I ended up reading it as a history late Bronze Age. Except for chapter 4 (which was for me an overly-detailed catalog of layers of destruction and rebuilding in various cities) an enjoyable account.

1In an unnecessary attempt to make things relevant, this is compared to our current interconnected world. At one point Cline loses track of the metaphor and refers to this as the first "truly global" trade network in the world, which is a slight bit of hyperbole for an area that sort of covers places touching the southeastern periphery of today's EU.

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Terror at the Shore

Terror at the Shore by Seamus Cooper

Terror at the Shore by Seamus CooperMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

The author of Mall of Cthulhu tells a story about a family that takes a seaside vacation at Dagon Heights, NJ.

Families should not take vacations at places called Dagon Heights.

Tongue-in-cheek horror tale (a riff on Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth, if you missed the reference), there aren't enough outright jokes to call this a comedy--it's more a very light thriller and reading it is a perfectly good way to spend an evening.

It could also double as the novel version of a teen horror flick (just as Mall of Cthulhu could have been the pilot for a Buffy-knockoff TV series.) There is the requisite morality play built in, but happily Cooper is enough of a mensch that in his world smoking dope and having sex are not the sins that get punished.

Friday, November 7, 2014

Battle Cry of Freedom

Excellent and very readable account of the Civil War. It starts at the end of the Mexican-American War, and covers the rising tensions tensions in the 1850s--including 'Bloody Kansas', the Dred Scott decision, and the splintering of American politics into a primarily sectional dispute. The war itself is primarily an account of the campaigns, interspersed with chapters on the economy, political disputes, emancipation and other domestic concerns.

Presumably because it's part of the Oxford History series, it ends rather abruptly with the end of the war in 1865, leaving the narrative thread that was leading towards complete emancipation (not to mention the black vote) incomplete, though sparing the reader the depressing story of the abandonment and reversal of those arcs during reconstruction.

Various points:

The song is jauntier than the book, which was often a brutally depressing read.

Presumably because it's part of the Oxford History series, it ends rather abruptly with the end of the war in 1865, leaving the narrative thread that was leading towards complete emancipation (not to mention the black vote) incomplete, though sparing the reader the depressing story of the abandonment and reversal of those arcs during reconstruction.

Various points:

- I hadn't realized how much the later war in the Virginia theatre started looking like WWI. Weapons had improved and soldiers had dug in, so assaults became brutal.

- This might have happened even earlier, but Union leaders in the east before Grant tended to retreat after a failure and Lee would pursue them. Grant simply held the line and attacked again.

- Along these lines, McPherson argues that suggesting Grant's goal was a war of attrition (where the Union was guaranteed to win) is wrong. Grant’s maneuvering and assaults were intended to push Lee out so he could be decisively beaten. Which failed until Sherman’s southern advance made Lee desperate, when it succeeded.

- Lee, Jackson, Sherman and Grant come off well as military leaders. McClellan as an excellent administrator with no nerve for combat and Hooker and Burnside as incompetents.

- Lincoln’s thoughts on slavery changed over his lifetime but very rapidly during the war. Even more dramatic were his thoughts on blacks where he went from an explicit (if fairly indifferent) racism towards being in favor of black voters and defending black troops and POW’s. (See also The Fiery Trial, which I should review sometime, for much more on this.)

- There were many morbid ironies in the war, among them that the South’s perseverance and early success guaranteed the end of slavery. If McClellan had won in 1862 slavery would have lasted in some form for a generation or two at least.

- The British elite were basically willing to recognize the South but wanted to wait until it was quite certain the North would admit they were stalemated, which they generally expected to happen ‘soon.’ Napoleon III wanted to recognize the South but didn’t want to go it alone.

The song is jauntier than the book, which was often a brutally depressing read.

Sunday, November 2, 2014

Hammered

Hammered by Kevin Hearne

Hammered by Kevin HearneMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

I thought this was easily the weakest entry in the series so far. What I thought was an ongoing throwaway joke ("Thor's a real asshole") is taken at face value and becomes the plot. I kept waiting for a punchline that never came.

Some of the individual scenes are good, though there's not enough of the wolfhound Oberon. The beer Atticus shares with Jesus is funny enough in concept to overlook mediocre execution.

Saturday, November 1, 2014

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Common Law & Public Accomodations

[I]f an inn-keeper, or other victualler, hangs out a sign and opens his house for travelers, it is an implied engagement to entertain all persons who travel that way; and upon this universal assumpsit an action on the case will lie against him for damages, if he without good reason refuses to admit a traveler.

–Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England

via LGM

Monday, October 6, 2014

Devil in the Grove

Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America by Gilbert King

Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America by Gilbert KingMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

I'm old enough that I became aware of Thurgood Marshall first as a Supreme Court justice--one of the two stalwart liberals on the court in the '80s. At some point (college?) I learned that he was also the lawyer who won Brown vs. Board of Education, which amazed me as it seemed like enough accomplishment for a lifetime, not a precursor to a long career.

This book goes back a step earlier in his career, pre-Brown, when he travelled the country as a senior NAACP lawyer, taking not only desegregation cases but also being one of the few men who would stand up in court for black criminal defendants being railroaded. It opens with him somehow getting an acquittal for black defendants accused after a riot, then getting out of town without being killed--a real danger in this case. Because their remit was not to be a general legal aid society, and because they had limited resources, he and his colleagues took only cases in which they believed the accused were innocent. Sadly there was no shortage of those in the late '40s, and the main narrative in the book centers on an egregious one in Florida.

The above makes it sound like this book is mostly about Marshall, which is what I thought when I started reading it. But it is at least as much about the corrupt sheriff Willie McCall. The book is written as such a gripping narrative that telling much about the case would feel like giving away spoilers for a seventy-year old series of events. But I will say I'm so used to civil rights narratives being framed as a story of triumphant progress that it took me a long time to realize, quite horribly, that the George Martin quote applied here: "If you think this is going to have a happy ending, you aren't paying attention." It has it's lighter moments and successes, and it's a story of an underdog fighting for justice, grippingly told, but it's not a feel-good book.

My only complaint is the flip side of it being such a good read--it's often written as a breathless you-are-there-narrative, not history. You read about what Marshall was thinking when he faced a probable lynching (roughly "It is never a good thing for a black man in a police car when the officers turn onto a dirt road at night") but it to get the source you need to look up the footnote (Marshall himself, in this case) and there's certainly no discussion about whether I should completely believe the story or maybe 90% believe it because maybe Marshall told a different version another time?

But this is a quibble. Even if you discounted everything that wasn't a matter of public record or agreed to by unsympathetic witnesses there's enough of interest and outrage to make this a phenomenal read.

Monday, September 8, 2014

Salt, Please!

I consider this one of the great TV rants:

Thursday, August 21, 2014

Mutants

Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body by Armand Marie Leroi

Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body by Armand Marie LeroiMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Near the end of this book the author pulls out the quote per molto variare la natur e bella--Nature's beauty is its variety--and it could be a motto for the book itself. Given that most of the book is about the human body developing dramatically abnormalities, usually during development, beauty is an odd word. I found some accounts difficult to read. But the ability for human biology to survive and sometimes prosper in so many different forms was just amazinga.

The book is a discussion of various conditions that have very visible effects--dwarfism, giantism, Siamese twins, people with no hands or feet, people with hands and feet but no arms and legs, people covered with more hair than Chewbacca, and so on. Some are fatal at birth, some at a young age, but most are not. A surprising (to me) number of people founded lines still prospering today--so a Chinese sailor missing the top his skull and clavicles founded a line that has several hundred descendants with the same symptoms.

If the existence of a whole family sharing such an unusual trait makes you wonder if scientists can do some sort of genetic analysis and figure something out about how genes interact with the body, well, answering that is the book's main concern. (Spoiler alert: Yes.) Most of the discussion is on gene expression and signalling pathways, in more detail than I expected. I'd call it roughly a Scientific American level of discussion. I'm not well qualified to judge the scientific soundness but in the small number of cases I knew anything at all Leroi seems to have done a good job presenting both conclusions and uncertainty.

The title--presumably picked by the publisher--is misleading though, as many problems are teratogenic or even nutritional and hove nothing to do with genetics. (Thalidomide and iodine deficiency induced issues, for example.) I don't begrudge "Mutant" for eye catching value but throwing in "genetic" in the subhead continues the annoying trend in popular science writing of implying everything biological is genetic.

Tuesday, August 5, 2014

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary by Caspar Henderson

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary by Caspar HendersonMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

This was not the book I expected when I ordered it, but I completely loved it.

I thought I was getting a coffee table book about biology with lots of pictures, instead turns out it's mostly words. (The hardcover is beautifully laid out, though.) The book is twenty-six essays titled around different, often weird, animals. Only some are primarily about their nominal subject. Some are riffs on biological features specific to the animals, others move into more general ruminations about folklore or philosophy or environmental hazards.

To take a couple examples, the opening essay is on the axolotl and spends around half the essay on medieval tales about salamanders dancing in fire and other interpretations of those amphibians--before describing a bit about evolution of the first land animals and how the tiny guys were doing cute little push ups back in the day, before getting around to saying something about the creature itself. Or, for humans, the distinctive feature he picks out is our feet--we're a two legged creature that walks instead of hopping and a lot follows from our bodies need to accommodate that. Chapters on octopuses, Gonodactylus smithii, dolphins and pterosaurs, on the other hand, are more straightforward zoology. (A few bits don't work that well, hence the book narrowly avoiding a 5-star rating.)

Since I have a visceral dislike for the sort of essay that starts with quantum entanglement and ends with the 'interconnectedness of the universe' or something, it took me a while to figure why the barely-science essays didn't bother me. (Beyond the fact that they often quite interesting on their own.) I think it's because Henderson clearly was fascinated by and respected the science; he knew the difference between when he was saying "This is what we've learned from science" and "This bit of science puts me in mind of this story I heard" and doesn't confuse the two.

In closing, here's a picture of a Yeti crab: .

View all my reviews

How could you not love someone with a smile like this?

I'm like six book reviews behind, but it's easier to post a picture of a paddlefish:

And this isn't one of your foreign exotic beauties, either--lives in the heartland of the USA.

But near extinction, dammit.

via PZ Myers.

And this isn't one of your foreign exotic beauties, either--lives in the heartland of the USA.

But near extinction, dammit.

via PZ Myers.

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

The Difference Between “Significant” and “Not Significant” is not Itself Statistically Significant

http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/published/signif4.pdf

A paper that I read years ago (via a Cosma Shalizi post on the file drawer problem) and then totally failed to find when I wanted to re-read it. Up there with the "No Free Lunch Theorem" as being simultaneously blindingly obvious and something that I'd never thought about.

It discusses exactly what the title says. A highly significant result may be indistinguishable from an insignifcant one, statistically speaking.

A paper that I read years ago (via a Cosma Shalizi post on the file drawer problem) and then totally failed to find when I wanted to re-read it. Up there with the "No Free Lunch Theorem" as being simultaneously blindingly obvious and something that I'd never thought about.

It discusses exactly what the title says. A highly significant result may be indistinguishable from an insignifcant one, statistically speaking.

Comparisons of the sort, “X is statistically significant but Y is not,” can be misleading.

Curse of the Mistwraith

The Curse of the Mistwraith by Janny Wurts

The Curse of the Mistwraith by Janny WurtsMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

There are some nice moments in this book, the first of lord-knows-how-many in a series, and maybe I'd even recommend it if it told a complete story. And was maybe half as long. But in too many ways it just comes off as a standard fantasy setup with prophecies and wizards and destinies. Maybe the later books will deliver a great payoff but I'm unlikely ever to find out.

View all my reviews

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

The Attempted Murder of Thurgood Marshall

In late 1946, Thurgood Marshall was an attorney for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and finishing the last of an amazing series of trials in Tennessee. Following race riots in Columbia, in a pre-civil rights court room and with all white juries, Marshall would still win acquittals for 22 black men charged in the aftermath.

The last trial ended in November, with the spectator area atypically empty. After another acquittal, Marshal and his associates left quickly and quietly, only to be stopped by the police on the way out of town. Marshall's associates--Looby, Raymond and a white attorney named Weaver--were told to leave town but Marshall was arrested for drunk driving.

The police turned down a dirt road. "Marshall knew that nothing good ever happened when police cars drove black men down unpaved roads." But Looby had followed the police instead of leaving town and managed to intercept the police sedan near Duck River; he stopped the car and refused to move. Frustrated, the police turned around and tried to book Marshall on drunk driving charges. A judge name Jim Pogue took a look at Marshall, decided it was BS, the smelled his breath and let him go. Pogue "stated that those offiers had come to the wrong man if they watned to frame Marshall. He said he was the one magistrate in Columbia who had refused to sign warrants for the arrests of Negroes during the February trouble."

By this point Marshall had realized why the courtroom was empty earlier in the day; the usual spectators were unwilling to take another defeat and had instead gathered at Duck River ahead of time for the planned lynching. This time Marshall and the other attorneys left town secretly, sending another driver in Looby's car as a decoy. Marshall made it out by the decoy car was in fact stopped and the driver beaten.

Source for this account: Devil in the Grove by Gilbert King.

Alternate version, not contradicting anything above but omitting the dirt road detour and the beating of the decoy driver, is here: http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=296

The last trial ended in November, with the spectator area atypically empty. After another acquittal, Marshal and his associates left quickly and quietly, only to be stopped by the police on the way out of town. Marshall's associates--Looby, Raymond and a white attorney named Weaver--were told to leave town but Marshall was arrested for drunk driving.

The police turned down a dirt road. "Marshall knew that nothing good ever happened when police cars drove black men down unpaved roads." But Looby had followed the police instead of leaving town and managed to intercept the police sedan near Duck River; he stopped the car and refused to move. Frustrated, the police turned around and tried to book Marshall on drunk driving charges. A judge name Jim Pogue took a look at Marshall, decided it was BS, the smelled his breath and let him go. Pogue "stated that those offiers had come to the wrong man if they watned to frame Marshall. He said he was the one magistrate in Columbia who had refused to sign warrants for the arrests of Negroes during the February trouble."

By this point Marshall had realized why the courtroom was empty earlier in the day; the usual spectators were unwilling to take another defeat and had instead gathered at Duck River ahead of time for the planned lynching. This time Marshall and the other attorneys left town secretly, sending another driver in Looby's car as a decoy. Marshall made it out by the decoy car was in fact stopped and the driver beaten.

Source for this account: Devil in the Grove by Gilbert King.

Alternate version, not contradicting anything above but omitting the dirt road detour and the beating of the decoy driver, is here: http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=296

Monday, June 9, 2014

Saturn's Children

Saturn's Children by Charles Stross

Saturn's Children by Charles StrossI bounced this up on my to read list because I was in the mood for space opera and someone mentioned it as a modern homage to Heinlein. Which is pretty spot-on, although we're not talking Starship Troopers, Farnham's Freehold or his young adult stuff. This is later-years Heinlein with plenty of sex in plenty of ways. (That picture to the left Goodreads provided gratis gives you a realistic idea of what era they're paying homage to.) It's a picaresque novel in space, decently plotted even if there were so many betrayals, body swaps and identical model robots that by the end I'd lost the thread on a few of the factions.

By far the most interest part is the setting, which is what I was most skeptical of going in. Stross imagines a world were humans have succumbed to something or other, leaving sentient robots behind. And while a few are quiet alien, they were generally built to think "like humans" and/or have internalized their original design goals that they keep on functioning in some facsimile of human society. But they weren't built just to be intelligent--they were also built to be servants, and the book tackles the implications of that in various ways.

Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime by P.G. Wodehouse

Uncle Fred in the Springtime by P.G. WodehouseMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

Time was I read a lot of PG Wodehouse, in the pre-web days where series that were oversupplied in used bookstore had a special place in my heart. I eventually had to stop because while I loved them I couldn't remember if I'd read Carry On, Jeeves but not Right Ho, Jeeves. And since all the plots involved Bertie starting himself accidentally engaged while trying to help out a friend and ended with him giving up on his desire to wear a green tie or white pants over the objections of Jeeves, I simply ran out of options. (A friend implied you could remember which book it was based on which piece of clothing Bertie sacrificed at the end. If there's not already an app for that, there should be.)

After twenty-five years later it seemed OK to start reading again, since the plots are interchangeable anyway and I certainly don't remember the jokes anymore. This book is from the Blandings series so a different cast of characters. Uncle Fred is an interesting sort--he's a sixty year old Earl with the recklessness, overconfidence and generosity of Wooster with something approaching the intelligence and savoir-faire of Jeeves. The rest are 20-somethings who got a little confusing, since it's too easy to think of Fred as everyone's uncle the romantic triangles get a little weird.

I'll make one slightly serious point: In my twenties the 'old ball and chain' stereotype of all women over 50 must have passed by unnoticed, but it got old this time around. One of those annoying period jokes that just didn't age well, especially when the nominally good-hearted hero indulges in quips that come off a bit mean-spirited today. The book could have used an Aunt Dahlia.

Stats for the PG Wodehouse app I mentioned:

Plot Keyword: Pignapping,

Number of brain specialists: 2

Number of non-impostor brain specialists: 1

Primary card game: Persian monarchs

Best phobia: Fear of lambs

Destroyed clothing: None. This is a Blanding book, not a Jeeves book. Do pay attention.

Worth Reading: Yes

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

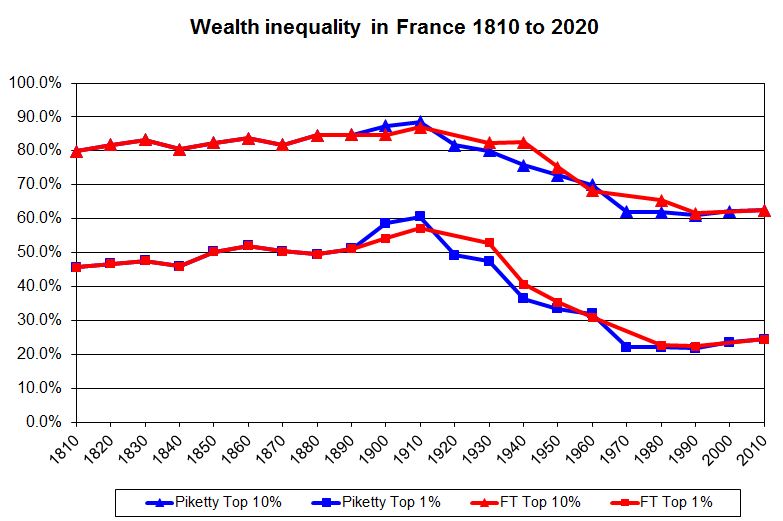

Piketty Criticisms I: Bad Data

I'm reading Piketty's book fairly slowly, with a bunch of others in between. Review eventually.

But a lot of debate is piling up as people take shots at it and defend it for whatever reason*. So thought it worthwhile to collect for later reference, even if much appears over my head.

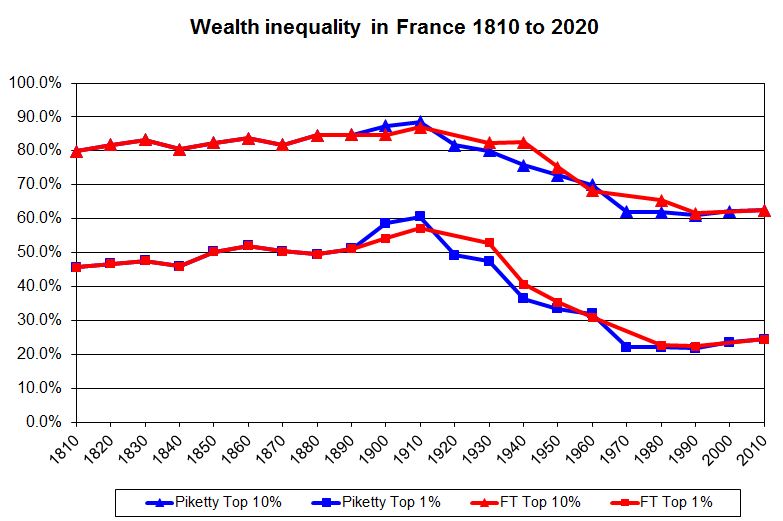

The red are the FT numbers and the blue is the Piketty line. They don't seem huge shifts in either case at this scale. Though to be clear the FT numbers for the UK show no upwards trend in any series so there is a question of how Piketty has deduced there is one.

First, a (paywalled so I can't read) Financial Times article seems to take aim at the data. And while I'm not going to try to venture an opinion on most of these discussions this one seems to be a bit of hatchet job, with over broad claims of massive errors while focusing on numbers which are not (or not clearly) wrong without bothering to assess their impact on the overall thesis even if they are correct†. The general claim is that Piketty's number don't support the claim that inequality has increased.

Lefty anti-capitalist article from Bloomberg has the most news-like take down, quoting experts to rebut the claim in non-opinion format. Krugman and others cover the obvious point that the increase in inequality--especially in the US--has been established by multiple data sources so picking on a single series isn't exactly withering. Slate's Moneybox covers the dispute in a few posts today. Yglesias has charts, showing both the irrelevant nitpicking in France and the potentially interesting debate about UK numbers.

The red are the FT numbers and the blue is the Piketty line. They don't seem huge shifts in either case at this scale. Though to be clear the FT numbers for the UK show no upwards trend in any series so there is a question of how Piketty has deduced there is one.

*"For whatever reason" of course includes but is not limited to criticism motivated by finding substantial errors. It's clear the political argument and trendiness of the work gives people a big incentive to find problems with it or point out that their observations made earlier are more insightful. As Henry Farrell at CT points out, many who "might have found the book interesting had it been an academic exercise" respond differently when there are higher real world stakes involved--which doesn't mean they are wrong, of course.

†Sooner or later I need to write my 'Science Haters' Guide to Science Criticism' and include this ploy as one of the key moves.

†Sooner or later I need to write my 'Science Haters' Guide to Science Criticism' and include this ploy as one of the key moves.

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Everybody Dies Alone

From Barcelona:

Fred: I remembered this razor ad on TV showing the hair follicles, like this. The first of the twin blades cuts them here. Then the hair snaps back and the second blade cuts them here...for a closer, cleaner shave. That we know. But what struck me was: If the hair follicles are going in this direction and the razor is too...then they're shaving in the direction of the beard, not against it.

So I've shaved the wrong way all my life. Maybe I misremembered the ad. The point is...I could've shaved the wrong way all my life and never have known it. Then I could have taught my son to shave the wrong way, too.

Montserrat: You have a son?

Fred: No. But I might someday. Then, maybe, I'll teach him to shave the wrong way.

Montserrat: I think maybe my English is not so good.

Monday, April 21, 2014

Caterpillar or Luchadores?

I might have become a biologist if we had the internet and so many pictures of colorfully bizarre animals when I was a kid. Probably less lucrative than working in pharma but nature is pretty cool at a macroscopic level too.

Here is a humble caterpillar (Phyllodes imperialis) that evolved a little Mexican-professional-wrestling-mask on its back, so when it's threatened it scrunches up, protecting its head and revealing it's super-powered alter ego.

(The white stuff is apparently supposed to be teeth but they don't work for me.)

via PZ Myers

The Iron Druid

Kevin Hearne's Hounded and Hexed:

A druid who's something north of 2000 years old has pissed off enough Irish gods that he moves to Tempe, Arizona to get away from them. Not that they can't get there at all, but there's not enough oak or ash or whatever it is they need to cross over easily. Unfortunately one of them finds him through the internet and crazy high jinks ensue.

I read this book and immediately got the next one in the series and read that as well. To be sure, "crazy high jinks" includes a lot of fantasy violence, but otherwise I think the book delivers exactly what my summary would imply. Even less complexity or shades of grey than a typical Dresden Files book, but it and the sequel are pulpy fast paced entertaining fun.

Oh, and did I mention the conversations he has with his Irish wolfhound?

A druid who's something north of 2000 years old has pissed off enough Irish gods that he moves to Tempe, Arizona to get away from them. Not that they can't get there at all, but there's not enough oak or ash or whatever it is they need to cross over easily. Unfortunately one of them finds him through the internet and crazy high jinks ensue.

I read this book and immediately got the next one in the series and read that as well. To be sure, "crazy high jinks" includes a lot of fantasy violence, but otherwise I think the book delivers exactly what my summary would imply. Even less complexity or shades of grey than a typical Dresden Files book, but it and the sequel are pulpy fast paced entertaining fun.

Oh, and did I mention the conversations he has with his Irish wolfhound?

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

Eat Once, Gain Weight Forever

Not that much to look at, the Convoluta roscoffensis is a flatworm that eats algae until the algae is producing enough nutrients through photosynthesis to keep the worm alive. Adults don't need to eat at all.

It seems somehow appealing, although upon consideration it's like the anti-diet--all the calories of a good meal with none of the taste.

The American

I'm not sure what I thought of The American as a whole. I know I didn't like most of it. Clooney is a hit man exiled to a small Italian town while trouble blows over. There is very little meaningful dialogue but many medium distance shots of him off center in a mostly empty frame to make it really clear how isolated he is, just in case his brooding and lack of human interaction was missed. The attitude towards plot can be summed up as roughly "You've all seen this story before. You'd be as bored as us if we spent screen time working through the details, right?"

But even if most of it felt like someone working from a film school textbook on melancholy, I was a bit surprised in the final scenes that I cared about the characters and they had some real impact. So not a complete dog of a film.

But even if most of it felt like someone working from a film school textbook on melancholy, I was a bit surprised in the final scenes that I cared about the characters and they had some real impact. So not a complete dog of a film.

Monday, March 17, 2014

Dust

Elizabeth Bear's Dust:

A generation ship breaks down and starts orbiting a dying sun, the inhabitants split into factions that start struggling for control of the ship--or just their personal fiefdoms--as the centuries drag on. This falls into a genre I've never quite gotten, science fiction that explicitly chooses fantasy trappings. Societies have a medieval structure with inheritance among families and knights going on quests, while genetic engineering and nanotech provide miracles and mythical beings and computer subprograms are like gods.

I continue to like Bear's writing and there are some nice narrative tricks around how things are perceived, plus an interesting take on the differences between love, trust and desire in relationships. But for me probably not worth continuing with the series. Certainly I'll exhaust some of her other works (including the excellent Eternal Sky series) first.

A generation ship breaks down and starts orbiting a dying sun, the inhabitants split into factions that start struggling for control of the ship--or just their personal fiefdoms--as the centuries drag on. This falls into a genre I've never quite gotten, science fiction that explicitly chooses fantasy trappings. Societies have a medieval structure with inheritance among families and knights going on quests, while genetic engineering and nanotech provide miracles and mythical beings and computer subprograms are like gods.

I continue to like Bear's writing and there are some nice narrative tricks around how things are perceived, plus an interesting take on the differences between love, trust and desire in relationships. But for me probably not worth continuing with the series. Certainly I'll exhaust some of her other works (including the excellent Eternal Sky series) first.

More Beasts

E, F, and G in the Book of Barely Imagined Beings were all disconcertingly alien, covering eels, flatworms and a smasher shrimp. It was actually difficult to read on a sunny weekend afternoon, especially since it followed the very charming dolphin chapter.

This, for example, is the shrimp Gonodactylus smithii:

It's got an appendage it uses to club things with, which shoots out at near-bullet like speeds, enough to break a human bone. Happily, despite the dirty genus name the 'appendage' is not its penis, but just a specialized limb. Apparently there are 'smasher' and 'spearer' shrimps, and the smashers want to be able to club through shells to get to their meat.

Most of the description in the book focuses not on its threatening bullet-finger, though, but its vision. It can distinguish polarized (in common with other marine species) and circularly polarized light (a unique ability), letting it see transparent animals and invisible-to-us features quite easily.

This, for example, is the shrimp Gonodactylus smithii:

It's got an appendage it uses to club things with, which shoots out at near-bullet like speeds, enough to break a human bone. Happily, despite the dirty genus name the 'appendage' is not its penis, but just a specialized limb. Apparently there are 'smasher' and 'spearer' shrimps, and the smashers want to be able to club through shells to get to their meat.

Most of the description in the book focuses not on its threatening bullet-finger, though, but its vision. It can distinguish polarized (in common with other marine species) and circularly polarized light (a unique ability), letting it see transparent animals and invisible-to-us features quite easily.

Friday, March 14, 2014

I picked up The Book of Barely Imagined Beings by Caspar Henderson. This an A-to-Z list of real animals, nominally modeled after a medieval bestiary so I assumed, quite reasonably I think, that it would be a coffee table book with lots of pictures. It is not. There are lots of words and very few pictures. It is shameful how publishers let people inflict words on their readers.

To make up for this, I am looking up the pictures on line. The axolotl, for example:

A salamander that looks cute, freakish, or disturbingly like a homonculus in the D&D Monster's Manual I had in the '80s, depending on your point of view. Sadly seems to be doomed in the wild (it's range was only Mexican lakes to begin with) but will survive in laboratories studying regeneration and among aquarium owners.

Other things learned: Apparently the first air-breathing vertebrates evolved to thrive in murky, shallow waters where (like our friend about) they could run around on their short stubby legs and do little push-ups to gulp in oxygen that was in short supply in the water itself. I'm not sure what I thought the driving force was, maybe just fish and beaches and something more like this:

To Say Nothing of the Dog

Connie Willis' To Say Nothing of the Dog:

This is a light novel that sends its hero time travelling to search for clues as to the whereabouts of the "Bishop's bird stump" for a reconstructed Coventry cathedral. The protagonists are historians and know the world through literature, which is convenient as the real world ends up performing much like a comedy of manners. There are a ton of self-aware references, from PG Wodehouse, to Arthur Conan Doyle's gullibility about spiritualism, to upper class idiocy, Lord Peter Whimsey, and eccentric Oxford dons. Add in some 'time lag' as an excuse for broader slapstick and it's a bit like a shotgun blast, but manages to keep a consistent tone. The resolution seems like a bit of a cop-out but that's not really the point. Very entertaining.

This is a light novel that sends its hero time travelling to search for clues as to the whereabouts of the "Bishop's bird stump" for a reconstructed Coventry cathedral. The protagonists are historians and know the world through literature, which is convenient as the real world ends up performing much like a comedy of manners. There are a ton of self-aware references, from PG Wodehouse, to Arthur Conan Doyle's gullibility about spiritualism, to upper class idiocy, Lord Peter Whimsey, and eccentric Oxford dons. Add in some 'time lag' as an excuse for broader slapstick and it's a bit like a shotgun blast, but manages to keep a consistent tone. The resolution seems like a bit of a cop-out but that's not really the point. Very entertaining.

Thursday, January 30, 2014

Julian

Review of Gore Vidal's Julian:

A novel presented as the Emperor Julian's unfinished memoir. For some reason I thought this would be about a libertine Roman emperor and involve a lot of satire at the expense of uptight Christian morality. Well, not just some reason--I knew Julian was the last pagan emperor of a now Christian Rome and would (1600 year old spoiler alert!) come to a bad end in a pointless, ego-driven war with the Persians. Well, I shouldn't indulge in ignorant stereotypes about late pagan vainglorious Roman emperors.

In point of fact Julian himself was a competent general and administrator, plus a fairly strict moralist and earnest, humane philosopher and ruler himself. The writing and characters are on par with Vidal's American historical novels--he's interested in characters and motivations more than unsubtle jabs. (There are some, but mostly in a running commentary by two scholars who have scribbled notes in the margins of the manuscript, often quite funny.) Julian is drawn as someone who wants to be an intellectual and philosopher, is really by temperament a monarch and general, and is just self-aware enough to realize the gap and regret it. There are some ideas that seem monumentally bad, though, which he's told are monumentally bad, which turn out to be monumentally bad--something in between tragedy and farce.

Not a quite a four star book because, while overall quite good, I'm not invested in Julian as a historical figure, and the supporting characters I know only from this novel, so it never engaged me the way Lincoln or Burr did.

A novel presented as the Emperor Julian's unfinished memoir. For some reason I thought this would be about a libertine Roman emperor and involve a lot of satire at the expense of uptight Christian morality. Well, not just some reason--I knew Julian was the last pagan emperor of a now Christian Rome and would (1600 year old spoiler alert!) come to a bad end in a pointless, ego-driven war with the Persians. Well, I shouldn't indulge in ignorant stereotypes about late pagan vainglorious Roman emperors.

In point of fact Julian himself was a competent general and administrator, plus a fairly strict moralist and earnest, humane philosopher and ruler himself. The writing and characters are on par with Vidal's American historical novels--he's interested in characters and motivations more than unsubtle jabs. (There are some, but mostly in a running commentary by two scholars who have scribbled notes in the margins of the manuscript, often quite funny.) Julian is drawn as someone who wants to be an intellectual and philosopher, is really by temperament a monarch and general, and is just self-aware enough to realize the gap and regret it. There are some ideas that seem monumentally bad, though, which he's told are monumentally bad, which turn out to be monumentally bad--something in between tragedy and farce.

Not a quite a four star book because, while overall quite good, I'm not invested in Julian as a historical figure, and the supporting characters I know only from this novel, so it never engaged me the way Lincoln or Burr did.

Monday, January 13, 2014

William the Silent

On C. V. Wedgwood's William the Silent

In 1568 William, a prominent local noble, led an army into the Netherlands to liberate his people from the Spanish king Phillip II. Two centuries later, George Washington would later be praised for simply keeping an army together during his revolution, but William would fail to do even that. His Spanish opponent simply avoided battle and, denied any success, William's money ran out and his army evaporated before the year was up.

At this point William could have ended as a minor footnote in history. Bankrupt and cut off from his allies, he worked mostly in vain to garner support for another attempt. A few years later, though, Spanish excesses would rekindle the revolt in the northern provinces and it was William's flag that they raised. The war for independence would ultimately last 80 years, and while William wouldn't live to see most of it he was the one who kept them alive by the slenderest of threads in the first few years--both by military means and by a decency in politics & administration that made the revolting areas far more orderly and just than the Spanish administrated provinces.

In Wedgwood's book, William himself comes across as a mix of the medieval and the modern. Raised to rule in a feudal state, he felt it natural that he would lead other men and also that he should serve a monarch--to such an extent that after he broke with the Spanish king, he went looking for another one. But he had an egalitarian streak that seems entirely anachronistic, a beacon of tolerance in the middle of the reformation, and humanitarian attitudes even in war during an unapologetic era. Ultimately the feudal attempts would all fail--indeed, his more traditional allies Egmont and Horn, who couldn't bring themselves to break definitively with the king--would be executed by the Spanish for having questioned the king. But the modern attitudes would lay the foundation for the Dutch state.

For those unfamiliar with her work, Wedgwood herself is a great writer, a historian doing "popular" (e.g., not academic) history in the '50s; she reminds me a bit of Barbara Tuchman. The book spends a lot of time on personality and narrative, the social issues that get more emphasis in contemporary history are only illustrated through attitudes of the players. And while I think diligently researched it's also sparsely footnoted, which you may count as a feature or bug--I count it as a bug, but probably my only complaint with the entire book.

Introductions

I'm sort of assuming that no one reads random blogs that don't cross-post and that this will act more as journal than anything else. If you have stumbled across this, expect book reviews and comments on movies when I get around to writing them--if I get one post a month I'll feel content.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)